John Novak

Prop Design

I’ve been working for the Jungle since 1998. My “Properties Manager” credit is more recent than that. (My primary title is “Stage Manager”.) At first, no one was officially in charge of props, and it fell on me and Bain Boehlke (the company’s founding Artistic Director) to gather the furniture, props, and set dressing for each production, often with others enlisted to help. I had no training in prop design, so it helped immensely that my entire first season (the final season in the Jungle’s original space on Lake Street) consisted of remounts of previous Jungle productions: the decisions and choices had already been made, and most of what was needed was in Jungle storage (although any remount involves some refreshing, upgrading, and rethinking). As the years went by, and especially after Bain’s retirement, my responsibility for props expanded. I still consider myself something of an impostor compared to people who devote their full energies to the profession (evidenced by my avoiding the “Designer” title).

But I’ve learned a lot in 20-plus years, and after tackling well-known prop-designer nightmares like You Can’t Take It With You and Noises Off, most shows can’t terrify me anymore, although time management can still be daunting -- stage management is a full-time job, so prop work has to happen before and after rehearsals, and during the actors’ one day off every week (making for frequent weeks, and occasional months, with no day off).

Like every technical aspect of a production, props are steered by interdepartmental concerns, and benefit from all forms of expertise: if it plugs in or has a battery, the lighting designer and electricians can be enlisted for input and help. If it’s something a character might wear, or that might coordinate (or clash) with what they’re wearing, the costume designer is asked to weigh in. If something is built into the scenery, the scenic designer and carpenters primarily design and build it. And of course the director is involved in every choice, and the actors deserve input, to ensure their props suit their character and their capabilities.

The starting point for all of those conversations and collaborations is the script, and what guides all of the designers is the director’s vision for the production.

Scripts vary widely in the amount of information they provide. A playwright may begin with an introduction that speaks directly to designers, with preferences for how literal the environment is, how sparse or dense, how tidy or messy. Or the playwright might be silent on those topics, preferring to give each production full license to make its own choices. There may be character descriptions that include some biographical clues or information about their personalities, lifestyles, or socioeconomics that will help guide the designers toward what a character’s physical environment, clothes or possessions might be. And the “stage directions” (any printed text that isn’t spoken) may or may not flesh out details like time of day, weather, and what a character is seeing or wearing or carrying or using or eating. And sometimes there’s nothing but spoken language, and any details about the environment are deduced from what the characters say.

Importantly, the stage directions themselves, or at least some of them, may not actually be written by the playwright: before a script is published, to help the reading public envision a play, the environment is sometimes described based on an early production. So anything describing how and when characters move or behave, or what their environment is like, might not be language generated by the playwright, but is instead taken from the production record generated by the stage manager, and then filtered through an editor. Most often the provenance is unclear. So stage directions can be considered a flexible starting point, or a source of inspiration, but sometimes the director, design team, and actors will agree to entirely ignore some or all of them.

The director’s vision can reinforce the descriptions in the script, or render them irrelevant. A director may choose to change the location of the action from one city to another, or to another continent. She may choose to produce Shakespeare in modern dress, or with minimal reliance on scenery and props. She may desire an environment that’s naturalistic, or one that’s highly conceptual. (Sometimes those sorts of choices are artistic, sometimes they’re driven by the economics of the production.) The designers then investigate and interrogate that vision, and translate it into specific choices.

Once it’s agreed that a prop is indeed needed, the process can proceed down several paths. For an everyday object like a drinking vessel or a writing instrument, I like to provide a few options to work with in rehearsal. Some choices are obvious and simple, maybe because the spoken language includes telling details. (Unlike stage directions, artistic license generally doesn’t apply to the spoken text; the actors’ lines are almost always preserved verbatim.) Other choices evolve through conversation with the director and actors about how the style and features of a prop might contribute depth, backstory and context to the character and environment, or whether there’s a message in how its color relates to the palette of the scenery, costumes, or lighting. Ultimately, every choice is important: when this character slurps black coffee from a chipped novelty mug with her granddaughter’s picture on it, while writing with a dull golf pencil, she’s a different person, or maybe the same person in a different context, from the character who sips coffee with oat milk and Stevia from a cup and saucer, and writes with an expensive refillable ballpoint.

My window displays a few selected props, and attempts to expose the collaborative process that determined how they were chosen and styled for use in a Jungle production.

Full image taken by Dan Norman of THE NETHER axe

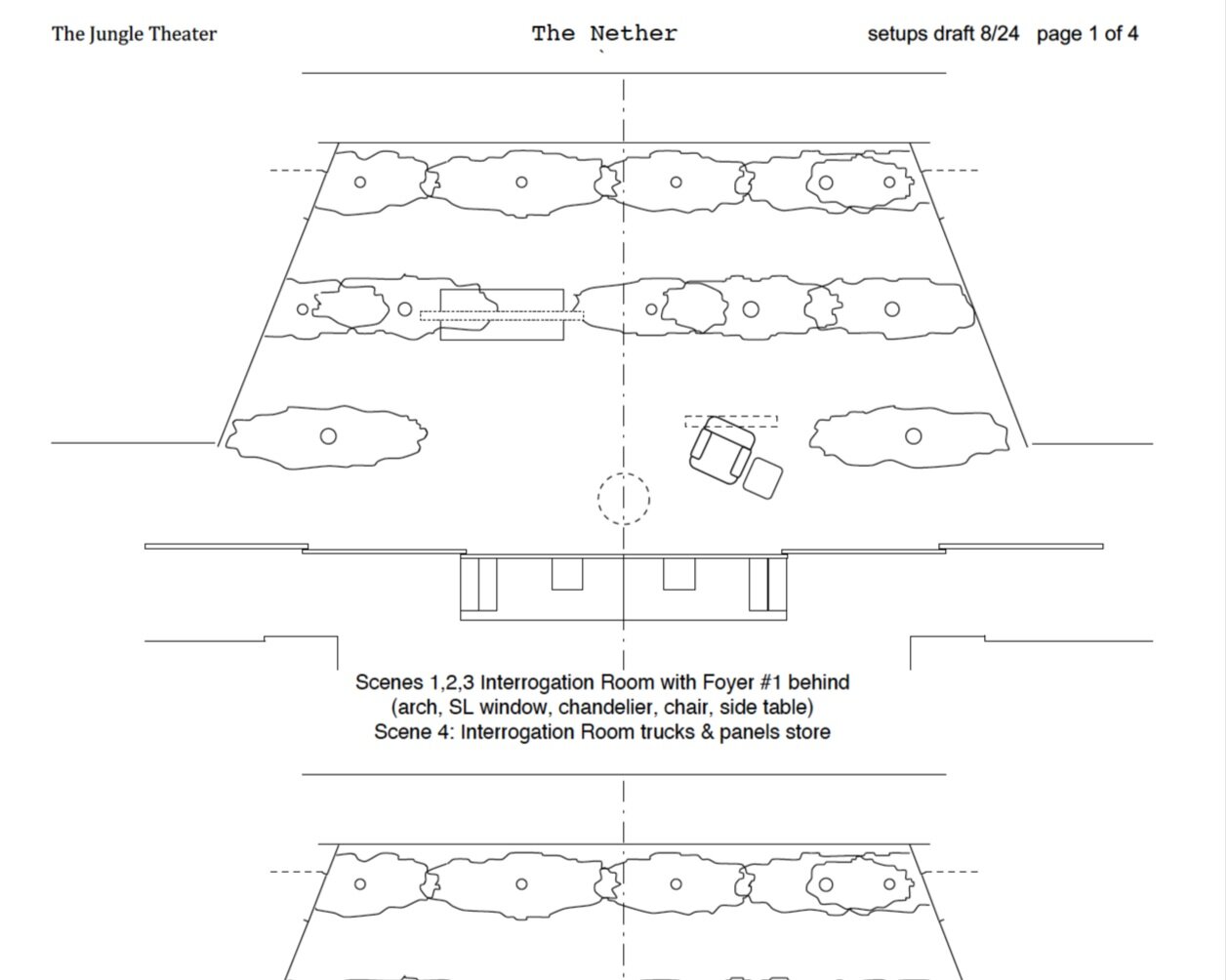

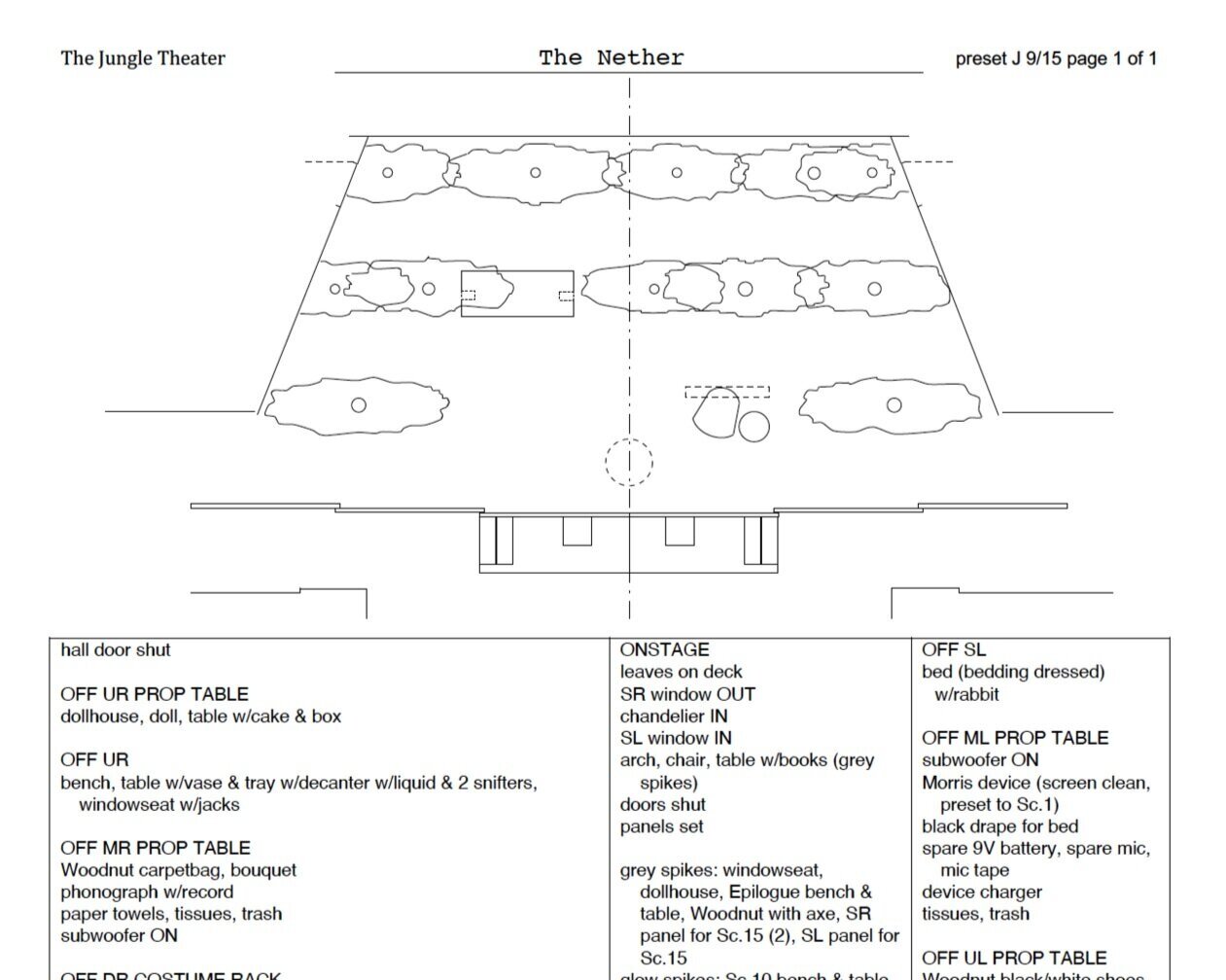

Prop Paperwork & Running Sheets

“Preset J” is the final version of the prop preset and crew running sheet. I update crew information as necessary during technical rehearsals, usually daily. For some shows with frequent changes or a more chaotic process, the final version letter is closer to the end of the alphabet. The idea is to keep the number of pages to a minimum, so objects and actions are described in a sort of shorthand.

The “Setups” document mapped scenery and props to help us keep track of where everything was supposed to be during tech, especially if we wanted to work scenes out of order. Ultimately its information got folded into the “Preset” to keep things simple during the run.

Iris Day: Cake of Ice

In one exemplary scene, Papa has digitally “made” her a cake of ice that will never melt. Iris puts her ear next to it and says she hears “the sound of tiny dwarves who live in snowy mountains singing falsetto.”

Papa says he can’t hear the sound, that “it must be only for children to hear.”

“Is that why you don’t want me to grow up?” Iris asks. “Because I’ll no longer hear the singing?”

John Novak and the Jungle’s interpretation of The Nether’s Iris Day cake is just one of many. Click here to explore other productions’: “The Nether Jennifer Haley cake.”

In a Dark Time

from The Collected Poems of Theodore Roethke (Doubleday, 1961)

In a dark time, the eye begins to see,

I meet my shadow in the deepening shade;

I hear my echo in the echoing wood—

A lord of nature weeping to a tree.

I live between the heron and the wren,

Beasts of the hill and serpents of the den.

What’s madness but nobility of soul

At odds with circumstance? The day’s on fire!

I know the purity of pure despair,

My shadow pinned against a sweating wall.

That place among the rocks—is it a cave,

Or winding path? The edge is what I have.

A steady storm of correspondences!

A night flowing with birds, a ragged moon,

And in broad day the midnight come again!

A man goes far to find out what he is—

Death of the self in a long, tearless night,

All natural shapes blazing unnatural light.

Dark, dark my light, and darker my desire.

My soul, like some heat-maddened summer fly,

Keeps buzzing at the sill. Which I is I?

A fallen man, I climb out of my fear.

The mind enters itself, and God the mind,

And one is One, free in the tearing wind.

Reflection From John Novak

The Nether was emotionally challenging on many levels, for actors and audience alike. Its setting, described as “soon” by the playwright, was disheartening: a dystopian future where trees are rare, natural beauty is extinct, and people seem to have retreated underground, spending most of their lives plugged into virtual reality. Many are much happier there, and “cross over”, abandoning their bodies entirely and becoming “shades”. Also, the characters are all morally repugnant on some level: murderous pedophiles and surveillance state tyrants. Central questions included whether a heinous act committed in virtual reality is “victimless” or not, and whether abusing the childlike avatar of an adult is the same as criminal pedophilia. Another challenge was that the story didn’t unfold chronologically. One fascinating feature was that many of the characters’ “lines” were wordless, and often a silent exchange went back and forth several times before anyone spoke again. It had the effect of suggesting an emotional choreography to a silence that another playwright may have rendered as [Pause.]

Near the end of the play, JuCoby’s Johnson’s character (actually the undercover avatar of Mo Perry’s character, the conflicted investigator whose methods ostensibly drive a suspect to suicide) describes entering the virtual “realm” his/her deceased father inhabited, and finding a book of poetry with one stanza highlighted. He/she recites the final stanza to his virtual host/her defiant primary suspect, and then there’s a stage direction: [A challenge.]

Theater-Themed Word Search

The daily New York Times crossword is one of my longtime addictions; during the extended pandemic shutdown I’ve gotten hooked on their Spelling Bee puzzle as well. (There are people who set an alarm for 3:00am Eastern Time so they can start solving as soon as a new entry is released online.) Here’s a theater-themed word search for anyone else who loves that little dopamine reward you get with a successful solution. Download a printable version here.

About John

After college, John worked as a freelance stage technician at venues around the Twin Cities, then started stringing together stage management contracts at opera companies in St. Louis, Boston, Dallas, Pittsburgh, and Tulsa. The companies would put him up in a hotel, or a furnished apartment, for a month or six weeks, then he’d move on to the next gig. Usually there’d be an interlude at home in Minneapolis, but most years he was out of town more than he was home. As several years went by, packing up and leaving got harder and he started looking for a stable gig in the Twin Cities, so he could spend more time with his favorite person: his partner Bradley Greenwald. A friend was planning to “get out of the business” when she finished her gig at the Jungle, so John asked for an interview and got hired for a show in the summer of 1998.

He’s a dedicated, assiduous worker, and usually pleasant to be around, so after that probationary show he was asked to stay for two seasons, to close out the theater’s original space on Lake Street and transition to the renovated space on Lyndale Avenue. If you’d asked him then where he thought he’d be in 20 years, he’d have had no idea. And no plan. Not really one for ambitious career or life goals (like amassing power and wealth), he gravitated to places where he could be of service and do work that was intellectually stimulating and spiritually uplifting. He preferred safe havens to hostile environments: the brainy, weird kid who was a wannabe extrovert was a favorite target of middle- and high-school hallway homophobes, and he had found sanctuary in choir, orchestra and the theater, so Fine Arts in some form was a good career fit. But “moving up the ladder” to become, say, a director or administrator, didn’t have much appeal, since those positions are more public-facing, and sometimes at a greater distance from the art-making itself. And, the longer he’s been at the Jungle, the more responsibility and input he’s been offered, and the company’s personality has evolved with changes in leadership; so it’s not as if he’s been doing the exact same thing year after year, despite keeping the same job title. So here he is, decades later, still at the Jungle. These days he’s a contented introvert, a private person, and still devoted to Bradley (they got married in 2014). He’s got his bad habits and character flaws, and gaping holes in his knowledge, but he’s working on all that. He loves science fiction, and cooking. When he eventually retires, in another decade or so, he intends to spend much more of his time out in Nature.

Credits

THE NETHER

by Jennifer Haley

Director: Casey Stangl

Scenic Designer: Lee Savage

Costume Designer: Mathew J. LeFebvre

Lighting Designer: Barry Browning

Sound Designer: C. Andrew Mayer

Projections Designer: Kathy Maxwell

Dollhouse Photo:

JuCoby Johnson as Woodnut

Ella Freeburg as Iris

Photo by Dan Norman

Axe Photos:

JuCoby Johnson as Woodnut

Ella Freeburg as Iris

Photo by Dan Norman

Stephen Yoakam as Papa

JuCoby Johnson as Woodnut

Photo by Dan Norman

Bunny Photo:

Ella Freeburg as Iris

Photo by Dan Norman

Cake Photos:

Stephen Yoakam as Papa

Ella Freeburg as Iris

Photo by Dan Norman

Stephen Yoakam as Sims

Craig Johnson as Doyle

Photo by Dan Norman